Part One: Counting Crows, Feuding Foes

by Ender’s Girl

A murder of Crows, a violent eruption of teen superpowers… and oh yes, those epic dogfights in the pelting rain and churning mud. Get a taste of high school action, J- and K-style.

Love is a battlefield, as Pat Benatar lustily declared in her 1983 song. Planet Earth is one too, according to John Travolta’s alien Psychlo character from his 2000 intergalactic flop.

Aaaand… so is high school, apparently – a premise that has spawned an entire genre of teen action comedy/dramedy on screens big and small. You need only transplant the barroom brawling and gangsta-mongering from mainstream action flicks into the tamer, more innocuous environs of an educational institution, and voila! – Battlefield High School.

The fact that these stories are set on a high school campus lends a patina of harmlessness to the violent scenarios — even though the plot actually has less to do with academics than with a bunch of overgrown kids fond of rearranging each others’ faces and dislocating random body parts as their after-school routine. To describe these types of productions (most rating not lower than PG-15 or its equivalent) as being “about high school life” is like saying that Titanic was about the, um, iceberg. The school setting isn’t really the point; films like these get made so that teen audiences — ah, those intense little creatures! — can live out their aggressive, hormone-fueled fantasies that continually chafe (futilely, it seems to them) against the carefully imposed strictures of a traditionalistic, “adults rule” society.

Korean director Kim Tae-gyun and Japanese filmmaker Miike Takashi tender two alternate interpretations of this proposition with Volcano High and the Crows Zeros, respectively — all diverting, popcorn-friendly fare, but each bearing the unique and heavily stylized stamp of its maker.

Crows Zero & Crows Zero II

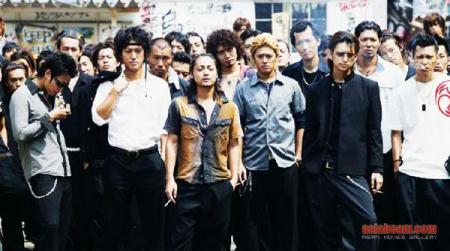

The Cast:

Oguri Shun, Yamada Takayuki, Yabe Kyosuke, Kiritani Kenta, Takaoka Sousuke, Kaneko Nobuaki, Miura Haruma

Directed by Miike Takashi / Toho Company, 2007 & 2009

In a Nutshell:

Senior toughie Takiya Genji transfers to the notoriously lawless Suzuran All-Boys’ High School. His mission? To vanquish the rival student gangs one by one and earn the title of Suzuran’s top dog – er, crow – and thus prove to his yakuza boss of a father that he has what it takes to inherit the family business. The biggest obstacle to Genji’s mission happens to be Suzuran’s strongest and most dangerous punk Serizawa Tamao and his head-bashing posse of high school hoods.

(SpoilLert: Moderately spoilery.)

“Looks like we’ve come to one crazy school.”

- “Squid Head,” Suzuran High freshman

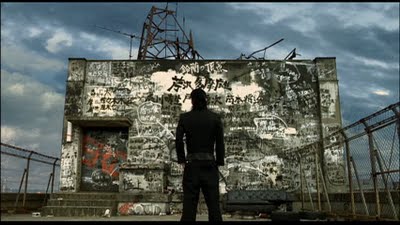

Drawing from the same cosmos as the immensely popular comics “Crows” and “Worst” by Takashi Hiroshi, the Crows Zero films unapologetically eschew the conventional fixtures of high school life – the classes, books, and teachers’ dirty looks, lol – for a combined four-hour slugfest in the mucky fields and graffitied corridors of the Serizawa All-Boys’ High School. The violence in both Crows Zeros is almost bacchanalian, each scene a “wild rumpus” among hot-blooded male youths determined to take the term “school spirit” to a whole new level.

The characters revel in the mutual hostilities with a casualness that will turn off — nauseate, even — viewers unaccustomed to director Miike’s ultra-violent style and wicked sense of humor: in one scene on the baseball field, a player swings his bat a bit too vigorously and accidentally bashes a teammate’s skull, a mishap that elicits no more than a flippant “Oops, my bad” reaction from the offending party. In another scene, Oguri Shun’s character, while learning to play darts with his new buddies, inadvertently lands one of his little projectiles in the dead center of another student’s forehead. Shun pauses in mild surprise — then nonchalantly turns away while the boy crumples cartoonishly to the floor, the dart sticking from his brow. Ouchy.

Not only is the violence in Crows Zero blithely brutal and untrammeled by morals or conscience (for the Suzuran delinquents seem to have none), but the fight sequences occur with a length and frequency that brook no debate about Miike’s not-so-ulterior motives as director. Apparently the word “restraint” is not in his vocabulary, and here he makes no bones about Suzuran High’s internecine battles being THE centerpiece and definitive aspect of these two films, up, up and above the more conventional elements of — oh you know, storytelling and character development. The plot is structured around the fights and not the other way around, so the end result is a chain of testosteroney brawls strung together by a marginally interesting story sorely lacking in sustaining power.

From a narrative point of view, Crows Zero feels like one long-drawn-out video game where Oguri Shun’s character Takiya Genji, in his bid to “conquer” Suzuran as he promised his old man he would, “levels up” from one student faction to the next until he finally squares off with the school’s baddest-ass gang leader Serizawa Tamao (Yamada Takayuki) and his cadre of goons. At first Genji assumes that he can defeat the mercurial Serizawa on his first day at school and have it done with by lunch break, but he realizes that in spite of the anarchy at his new school, there is a strange governing hierarchy and unspoken code of honor that everyone inexplicably adheres to: one has to earn the right to challenge an alpha like Serizawa by first vanquishing the lower-tier gangs – or groups that are younger or have already been defeated by the stronger factions.

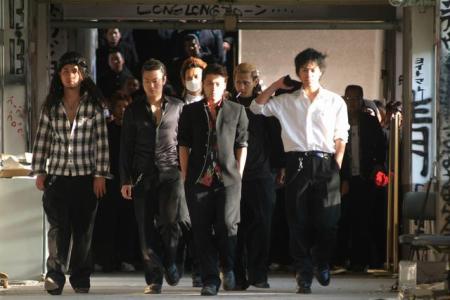

You soon realize why Suzuran High has earned the moniker “a school of crows” – and it isn’t just for the black school blazers and spiky-plumed hair that the students sport. Beyond the punky fashion the boys of Suzuran High are most like their corvid counterparts in their distinct patterns of social behavior, crows being intelligent and highly territorial birds that live in tight-knit community groups – or warring factions, if you will. Crows are also observed to be more aggressive than their cousins the ravens, often encroaching on and even invading other groups’ breeding ranges – features that make this analogy perfect for the studentry of Suzuran High.

The Tale of Genji

So after learning the lay of the land, Genji attempts to systematically win the allegiance of the heads of the various gangs, a lone general in search of an army to call his own. He can anticipate the final showdown to be with none less than Serizawa Tamao, and knows that it will all boil down to a numbers game between his men and Serizawa’s. Thus, Genji needs allies – soon. He meets an unlikely mentor in Katagiri Ken (Yabe Kyosuke), a buffoonish, underachieving local yakuza who takes a shine to Genji after the strapping senior handily whups Ken’s butt early on in the film. Himself a Suzuran dropout, Ken sees in Genji the school champ he always wanted to be but never could — because he simply wasn’t good enough. So he takes Genji under his wing, so to speak, and helps the boy — er, man really — strategize his plan of attack – often with comical (or trying to be comical) repercussions.

One by one, the heads of the rival gangs capitulate to Genji’s high command, though not without putting up a fight (they wouldn’t have gotten to where they were unless they were that tough, anyway). Genji employs a variety of methods to accomplish this: he uses his brawn to defeat Chuta (Suzunosuke) of Class E, his brains to win over the socially – and sexually – inept Makise (Takahashi Tsutomu), and sheer tenacity to sway the wily blond Izaki (Takaoka Sousuke). With three sections now swearing fealty, Genji’s alliance — bearing the chuckle-worthy, only-in-Japan-LOL name of “Genji’s Perfect Seiha (Succession)” or GPS for short — though untested, seems assured. The only wild card is Bando (Watanabe Dai — yes, Ken’s son), the fiercely independent boss of the biker gang calling themselves The Armored Front (go figger).

Even with the alliance, GPS remains outnumbered by Serizawa’s army 100:70 — and it goes without saying that Serizawa and his men will only budge from the school’s top berth — or perch — over their dead little punky bodies. Serizawa’s deputies are an equally formidable bunch: his BFF and loyal wingman Tokio (Kiritani Kenta), the devious Tokaji (Endo Kaname), the J-reggae mon Shoji (Yusuke Kamiji), even the synchronized Mikami Brothers (who may well be the J-punk version of the detective duo Thompson and Thomson from the “Tintin” comics) — fearless bruisers all, and who will not back down without a fight.

Perhaps the problem with the Crows Zero narrative is that there are just too many characters slugging it out for your attention. Unless you’re a hardcore fan of the source material, your first viewing will leave you scratching your head at this blur of all-look-samey teenage thugs who do nothing but kick each others’ heinies, strut down defaced school corridors, smoke like chimneys, glare and growl at nobody in particular, smoke like chimneys, and kick each others’ heinies. Or worse, you’ll doze off during the non-fighting parts and wake up only when the over-the-top sound effects of thwacks and punches jolt you back into the movie. It took me two-and-a-half viewings until the Suzuran denizens could actually be distinguishable from one another — and even then I still didn’t care about their individual threads. The whole thing felt like I was looking over someone else’s shoulder while they played a video game that was technically impressive, exciting and splashy, but emotionally uninvolving.

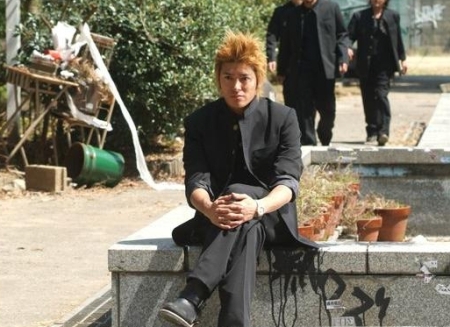

Much of the problem has to do with the movies’ protagonist, Takiya Genji. Sure, Oguri Shun is ultra-cool and unflappable in the Crows Zeros, looking fierce in his black blazers and track suits and sporting that mullet-with-cornrows hybrid, his lanky frame swaggering through the corridors… but character-wise? Not sympathetic or engaging enough to win the viewer over — something any scriptwriter and director worth their salt must keep in mind especially in a production such as this one, where it’s clear who the Hero and Villain of the story are. There’s an unattractive hardness to Genji instead of the gritty resolve I was looking for, more flint than steel. And his aloof personality crosses the no-no-for-heroes line into downright churlishness — which is why I found it hard to understand why anyone from Suzuran would want to follow Genji instead of Serizawa the Terrible, who at least knew how to laugh (albeit maniacally, lol).

There was nothing in Shun’s portrayal that made me want to root for Genji. Even his comical moments — to offset the tough-guy exterior, I suppose — felt incongruous to his surly demeanor. (When Genji cries bitterly after Kuroki Meisa’s character tells him off in one particularly long and unamusing scene, I only rolled my eyes.) The only time that I felt Shun/Genji delivered the comedic goods was the scene where he defeats Chuta of Class E while reading from a notebook that his yakuza friend Ken has supplied. So Genji bursts into the Class E room, takes a quick look at his cheat sheet and growls, “All right, who’s in charge here?” After Genji handily wipes the floor with the unsuspecting Chuta — the poor chump never had a chance, lol — he pauses as if trying to remember what to do next, then sneaks a peek at Ken’s lines before continuing, “As of today, this is my class. If you follow me, you’ll see what dreams are made of.” LOLLL. This scene was extremely funny because Shun kept deadpanning the whole time and neither the actors nor the director went overboard with the delivery and execution.

Genji’s romantic sub-arc with the feisty Ruka (Kuroki Meisa) remains underdeveloped throughout the two Crows Zero films. Too bad, ‘coz the chick is hawt. Though mostly clad in a simple T-shirt and jeans, Meisa smolders in her scenes — which aren’t that many to begin with. She performs three songs in the Crows Zeros (she sings at a bar, y’see) and her R&B routines are slinky and subtly sexy without going OTT vampy or sexed-up. But Ruka’s scenes with Genji’s fizzle rather than sizzle — though not for her lack of trying. Genji never seems to appreciate Ruka as he’s too self-absorbed in his angst, always at the bar nursing a beer and brooding over his next step in schoolwide domination. Their only cute moment that can legitimately be called A Moment is the time Ruka rehearses onstage with her backdancers and Genji watches her from his perch on the bar’s staircase, and their eyes meet for a split-second — but only a split-second. Anyway, I doubt the writer had any real romance in mind as Ruka and her friends, pretty young things all, function mostly as glorified sexual objects — which isn’t surprising given the target shounen market of these two films.

I was more invested in Genji’s relationship with the adults — his mafioso of a dad, and Ken the Underachieving Gangster — than in Genji himself. The sub-arc involving Ken, Genji’s dad Takiya Hideo (Kishitani Goro) and Ken’s boss (and the senior Takiya’s mortal foe, played by Endo Kenichi) provides an interesting diversion amid the mind-numbing high school mayhem, and one of my favorite scenes from the first movie is the time when Ken visits Genji’s dad at home, warning him that his own boss has ordered him to stiff Genji and thus trigger an all-out mob war.

Another more plaintive reason for Ken’s visit — a risky move to begin with that will ultimately cost him… well, everything — is to dissuade Genji’s dad from goading his son to pull off the unprecedented feat of total Suzuran domination — as a precondition for inheriting their crime organization, the Ryuseikai. After listening to his former underling’s entreaties, Takiya Hideo gives this pithy answer: “If he has what it takes to conquer Suzuran, I’m sure he’ll choose not to,” making the audience exhale a collective “aaahhh” as comprehension dawns that this whole thing is one big reverse psychology stratagem meant to set Genji on the path to true self-realization. Kishitani Goro as the elder Takiya has few scenes but manages to hold your complete attention in each one. You sense the yakuza power that emanates from his compact frame as much as you understand his (well-concealed) fatherly concern for his only — and apparently motherless — son. Their parent-son relationship may be atypical, but it’s one of the few things in these movies that feel real and unaffected.

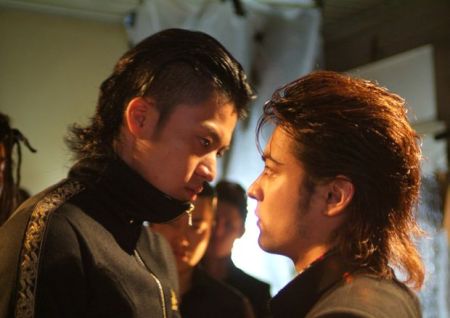

Serizawa: Sympathy for the Devil

But above all it is Yamada Takayuki who steals the thunder from everyone else. He’s too good for this vehicle, OWNING every single freakin’ scene he’s in with an onscreen presence that — despite his less-than-imposing height — compels and captivates. Which is weird because I never found Yamada to be particularly cute or prepossessing. His take on the volatile Serizawa is a fiendish delight to watch (and I suspect the writer had MOAR fun thinking up this role than he did Genji’s character). Serizawa Tamao is a young (mad)man unlike any other: always flat broke; a compulsive mah-jong player; fond of wearing those ridiculous floral shirts in lieu of the school uniform; quick to laugh with uninhibited glee over puerile matters — like getting a rare mah-jong combination, for instance — but possessing a lucidity that glimmers through the cracks in his psychotic shell; savagely violent (i.e. likes to play human bowling on the school rooftop) but well above the dirty tactics that some of his deputies later resort to.

In contrast to the morose, monosyllabic Genji who paces about with a giant yakuza-shaped chip on one rangy shoulder, Serizawa just feels — so alive and bursting with personality, from the bunched up sleeves of his blazer right down to his aversion towards footwear, lol. In Crows Zero II we see that Serizawa has sunk so far below the poverty line that he now squats on the side of the road, his living accoutrements strewn haphazardly on the pavement — although bumhood does not seem to deter him from his favorite pastimes of gambling, playing darts and chillin’ with his homies (especially Tokio). Barefoot, rumpled and clad in those rolled-up breeches, his hair wild and unkempt, Serizawa resembles a homeless hobbit instead of Suzuran High’s top toughie (or ex-top toughie, as this is in Crows Zero II) — and oh yeah, the height may have something to do with it too, lol. (He’d be right at home with the Lord of the Rings cast, ordering “a pint o’ ale” at the Prancing Pony, hahahaha.) When Genji intrudes on a particularly charged moment on Serizawa’s turf that involves a rival school, he curtly tells Serizawa, “Stop acting all cool you hobo,” LMAO.

Serizawa Tamao is in many ways a deconstructed villain who actually ends up garnering more sympathy (in my book, at least) than Shun’s character ever does. What makes him simpatico despite the diabolical rep is the humanity in those bottomless sloe-colored eyes, that manifests itself in the less frenetic moments in between fights… the flare of disillusionment after a trusted lieutenant betrays him, or the quiet hurt when his bosom buddy Tokio lies to him about the state of his health in the hospital parking lot. Serizawa may be a monster, but he’s a monster with a kokoro — and you appreciate how the Crows Zero films show this sensitive side instead of chucking him down the cardboard-villain route.

Crows Before Hoes!

Serizawa’s biggest chink in his armor is his friendship with his staunchest ally Tokio (Kiritani Kenta). First I just want to say how LOL it was of the writer (or director?) to make Tokio wear white 95% of the friggin’ time, while Serizawa, Genji et al. were in black — oooohhh the metaphors the metaphors!!! Lolz. Though unswervingly loyal to Serizawa, Tokio doesn’t hold back in advising reason and temperance — and I love how Serizawa respects that about him, as do the other members of their coterie. Kiritani Kenga makes his character likable without forcing his way with the viewer, and you do believe that his closeness to Serizawa, as different as these two are, is as real and well-valued as any good bromance out there. The sunset scene between Serizawa and Tokio, a welcome respite amid the merry mayhem of the story, is a terrific way of showing just how deep their mutual affection and respect lie.

Tokio also happens to be — surprise, surprise — Genji’s friend from junior high, which naturally tosses an interesting dynamic — a platonic love triangle, if you will — into the Genji vs. Serizawa enmity. Complicating matters even more is Tokio’s wee little secret of a brain tumor, and shots of him going through surgery, juxtaposed with the climactic battle scene at the end of Crows Zero, further fuel the drama by raising the stakes between Genji and Serizawa.

The pièce de résistance of the first Crows Zero movie is this final face-off between Genji’s GPS and Serizawa’s own army – or roughly twenty minutes of nonstop ass-kicking and furious fisticuffs right there on the roiling mire of… the Suzuran High schoolyard, now virtually unrecognizable in the gloom and the rain. The battle rages for the better part of the afternoon and well into the night while the fence-sitters watch from the school building. The indelible moment for me occurs at dusk, when the dull-red sun sets over the muddy field, now littered with the spent, groaning bodies of these fallen soldiers, and it casts a devilish light on the face of Serizawa, this madman who is just a few hours away from defeat. It is a most bitter pill to swallow when the better man – Genji – wins out in the end, although the happy news that Tokio has made it through his brain operation takes some of the sting off Serizawa’s drubbing. The background track “Into the Battlefield” by Otsubo Naoki sets the perfect tone to this climactic finale with the distorted bass beats and edgy guitars strongly reminiscent of the opening riffs of a Rage Against the Machine song or the P. Diddy-Jimmy Page collab “Come With Me.” [Listen to “Into the Battlefield” below:]

So Genji crushes Serizawa, forcing the latter to concede victory. Game over? Far from it, actually. Defeating the Serizawa faction is only one obstacle to schoolwide dominion, for Genji must now beat the Rinda-man, this 12-foot-high freak o’ naycha who technically belongs to the Second Year but dwarfs the entire student body — Serizawa most of all, hihihi — and possesses erudition and lore going back through the ages, lol. You could say the Rinda-man represents the very institution of Suzuran High, indestructible and immovable as a mountain, almost this elemental force that nobody can or will ever take down. He doesn’t actively begin fights, but will readily — and impassively — send you to your Maker should you sound the challenge. And he’s mysterious, too!!! — and only pulls back his trademark cowl on two occasions: when he fights, and when he dispenses philosophical truths to the foolish little mortals of Suzuran, but when he does so he reveals a smooth angelic face framed by a shock of golden curls, like Little Lord Fauntleroy on mega-steroids, lol.

“You fight and you fight — and then you graduate,” the Rinda-man tells Genji before beating him to a pulp for the nth time. In Crows Zero II the giant reiterates his stand: “Your enemy is not me. If you destroy everything, you’ll have to start again from scratch.” Here lies the philosophical core of the Crows Zeros: the existing social order at Suzuran High, with its tenuous equilibrium of rival gangs and power sharing, is still the best arrangement there is. As it is with Life, you can’t conquer it all, you can’t have it all, so the next best thing is to find meaning in the struggle itself. It’s all very existentialist-y to me, but whether or not you agree with this credo, you’ll appreciate the fact that the writer at least tried to temper the films’ unbridled violence with something profound and thought-provoking.

So the first movie ends with Genji having a go at the Rinda-man… and another, and another. And this is exactly where the sequel picks up several months later: Genji’s GPS underlings are feeling restless during the deadlock as their ultimate dream of school conquest is put on hold until their leader can finally dispatch Gigantor — er, Rinda-man. (Same thing.) But this inactivity is dangerous because some of the students have begun to doubt Genji’s abilities to unify Suzuran, while the other rival factions (like Serizawa’s for instance), though held in check for the time being, continue to watch for cracks in the GPS alliance and will not hesitate to seize an opportunity once it presents itself.

Suzuran and Housen: “Two schools, both alike in dignity. In Fair Nihon where we lay our scene. From ancient grudge break to new mutiny. Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean…”

The lull at school is shattered when Genji unwittingly breaks a two-year peace accord between Suzuran and the Housen All-Boys’ High School, a hotbed of hoods sporting white school uniforms and either bleached or shaved hairstyles. Apparently back in the turbulent days of the pre-Genji Era, some Suzuran dude named Kawanishi (Abe Shinnosuke) stuck a knife in the gut of the Housen numero uno, this thewy ox of a man who looks closer to 40 than 20, in other words more Batista than… Bieber. Ox-man dies (tsk tsk), bringing the official Suzuran-Housen casualty rate to 1 death out of 93748387487 battles — which is really NOT SO BAD, lol. The punk with the knife gets packed off to juvie hall but is released after two years (now the Age of Genji), not knowing that the Housen hoodlums are bent on retribution.

The current head of Housen is Narumi, played by that greasy, stringy, beady-eyed opium peddler from Buzzer Beat, Nobuaki Kaneko. With the peace treaty broken, Narumi incites the Housenites to avenge their fallen leader’s death by declaring all-out war. For starters, they ambush the Suzuranites in various locales in the city, the ultimate goal being their rival school’s total annihilation. It’s an interesting spinoff plot for a sequel, only it begs the question of how NOBODY from Suzuran ever briefed Genji about their bloodstained history with Housen after he became the de facto top crow at Suzuran. That Genji wasn’t the least bit aware of this vendetta the whole time he was at Suzuran — so that he had to learn the skinny from his bartender-friend — makes the sequel’s entire premise flimsy right from the start. It’s rather obvious that the writer was making up the Crows Zero cosmos from movie to movie.

That aside, the Crows Zero II story line gets bogged down by all these extraneous sub-plots involving characters that have no place in the sequel’s grand scheme of things. There’s this messy, convoluted arc where Knife Boy Kawanishi is revealed to have long-standing ties to the ex-gangster Ken, now enjoying his second lease on life in some fishing village. Knife Boy thinks Ken really did get stiffed by the yakuza boss, blahblahblah, but for some reason ends up working for the same don, who then employs him to take out the Ryusaikei head — who just so happens to be Genji’s dad. So Pops almost croaks after the the assassination attempt and Genji goes all Michael Corleone on him, but less cool ‘coz of his major meltdown in school that convinces some of his allies to bolt GPS. Knife Boy sneaks into Genji’s pops’ hospital room to finish off the job, but Reformed Gangster Ken arrives in the nick of time to stop Knife Boy from the dastardly act in a scene that’s as heavy-handed as it is downright hokey.

Meanwhile, the Housen hoods are THIS close to a complete rout of Suzuran High (makes you wonder what their terms of enslavement would be… forced labor in the Housen mines? annual tribute in the form or gold, spices and nubile dancing girls? lol), thanks to their Ultimate Secret Fight-o Weapon of Mass Destruction, a deceptively waifish, androgynous boy named Ryo who looks EXACTLY like Bi (yes, as in “It’s Raining” lol) and carries an umbrella to boot (what did I say? “It’s Raining!!!” lolol) and who would creep the hell outta me with that dispassionate, impersonal way he’d pound the Suzuranites’ faces into meat patties, only stopping unless Narumi told him to. Bloody creepy hell.

Miura Haruma (oh! well… hello there! didn’t expect to see you here!!!….. <LIE.>) plays the slain ox-man’s younger brother Bitou Tatsuya who goes against his “I’m a lover, not a fighter” (lol) pacifistic nature when Narumi prevails upon the fresh-faced freshman (eheheh) to officially sanction Housen’s declaration of war, knowing full well that more fighters — I refuse to call these thugs “students” lol — will rally behind the Bitou name. I honestly don’t know why Miura accepted this project when his entire exposure amounts to four short scenes, two in the smelly, sweaty Housen dojo, another on the Housen schoolyard (site of Crows Zero II’s climactic clash) and lastly on the school’s rooftop during the thick of the battle. How do you even describe his involvement in this movie… it’s more sizable than a cameo but smaller than a supporting role. Either way, Miura barely makes a dent.

Anyway, I’ll admit that I may have acquired the Crows Zeros for Yamada Takayuki and Oguri Shun (after all, I became a fan of theirs way before Miura and I were ever… acquainted, lol) but I finally popped the DVD into the player because of… Miura. But after having been desensitized to all the pseudo-carnage in the first movie, I’d forgotten he was even in the sequel… until the minute the boy walked into the Housen dojo, that left arm swinging slightly more than the right, and I knew it was him heh heh heh. (Yes, E.G. the Creepy Cougar strikes again, BLAHBLAHBLAH sowhatelseisnew.) I just was NOT digging the hair, which alternately resembled an albino octopus wrapped around his crown, a yellow doily, a gay yarmulke with tassels, and (as EstherM of JDorama.com put it) “overcooked spaghetti thrown by one angry Italian mamma,” lolol.

As much as I love the mild, wholesome Miura image in my head, I didn’t like how his character remained above the fray, unsullied by the brutality while everyone else got down and dirty, wet and wild on the battleground. Instead, there he stood on the edge of the field with that funny halo around his head, gravely surveying his troops before they marched off to war, so pale and so pure against the surging melee of dubious-looking teenagers caked in sweat and gunge and other unmentionables. Seriously, they shoulda just let the boy fight in the mud, y’know.

So how does it all resolve in the end? After nearly running the GPS into the ground, Genji finally learns to eat crow (hyuk hyuk) and gives a heartfelt apology over Suzuran’s PA system, causing his disgruntled men to look at each other and go, “Awww he’s leader material again, so now we’re ready to bleed and die for him yay.” So that’s how Genji unites all the warring factions of the School of Crows, and with their combined forces, he and Serizawa — aka Suzuran’s Two Tops (lololol) — are unstoppable on the battlefield — even if they’re right on the Housen High turf. At the end of the day the Crows go home bloodied (and resembling evil psycho clowns with their chalky, dust-caked faces and vermilion lipstick tomato paste) but definitely unbowed, and alive to fight another day.

As an extended video game, the Crows Zeros deliver the goods in all their preening, cawing glory. The movies are slickly entertaining and director Miike makes up for whatever narrative shortcomings with his relentlessly edgy, hyperreal style. And as immoderate and gratuitous as the action scenes are, they do not fail to impress in their execution and choreography. You can hand it to Miike for crafting his fight scenes with the same precision and eye for perfection of a seasoned ballet master orchestrating a high-profile dance performance. Barring a number of shots where the fists and faces of the students don’t quite connect (good acting though, lol), the stuntwork, camerawork and special effects appeal on both visual and visceral levels.

Furuya Takumi’s cinematography and Hayashida Yuji’s art direction in the first Crows Zero help create the gritty desolation of the Suzuran High landscape, mostly in muted grays with garish orange and red accents — a style that bleeds into the other sets i.e. the Takiya living quarters, the pool hall hangout, and the bar where Ruka works. Whereas the production team in Crows Zero II used a splashier, brighter color palette, very Gokusen-esque and I do not mean this in a good way. Needless to say I preferred the cinematography and production design in the first movie as they more closely mirrored the mood and spirit of the films’ titular birds; plus the cruddy surroundings and dismal, unwelcoming atmosphere of the school campus helped intensify the feel of the gloom-and-rain-soaked fight scenes.

But my biggest criticism of the Crows Zero flicks lies in the credibility of the world that the manga writer, the movie scriptwriter, and the director all had a hand in fashioning. I’m well aware that the story’s setting was intentionally constructed to be this pseudo-dystopia where the law of the Suzuran jungle (“Screw homework, just fight your way to the top!”) trumps all other laws (including those of basic physics). In this sphere of reality all adult presence is virtually absent from society and the students enjoy complete autonomy from their parents and teachers (and the poor little cringing things aka the school faculty appear in a brief scene at the start of the first movie, but hightail it home when the yakuza come a-calling for Serizawa, tsk), leaving the Suzuran campus a wasteland of vandalized walls and dilapidated, overturned desks.

Which made it hard for me to accept this physical reality: I couldn’t reconcile the ultra-liberal, anarchic world of Crows Zero with the sheer illogicality of students who had no qualms about terrorizing their teachers — or whoever was left of the decimated faculty — but religiously got up every morning to wear their uniforms and go to school. LMAO. A part of me kept laughing insanely the entire time these films were playing. I know some viewers have taken this seemingly minor hiccup in stride and attributed it to the governing rules of the Crows Zero-verse, but apparently these rules do not factor in good old common sense. I thus had great difficulty believing in this world because it didn’t feel real, just a nominal, one-dimensional backdrop for all the juvenile scrapping. Even the Suzuran/Housen students themselves felt phony, especially all of the extras and most of the cast who undoubtedly played the oldest high schoolers known to man. (Some actually had receding hairlines, lol.)

Besides, how can you take these movies seriously when they come with a corny child-friendly safety net? For one, despite the bone-crunching brawling nobody ever dies in the Crows Zeros (except for the flashback stabbing scene in the sequel), obviously on account of the students’ adamantium skeletons and instantaneous self-healing abilities, durr. Another sanitized aspect is the way the writing moralizes on how fighting mano-a-mano is essentially more ethical than fighting with weapons — never mind that people die either way. Basically the films’ message to the adolescent audience is, “Don’t try this at home, kiddos! You can beat the crap outta one another, but using knives is a no-no!” In one scene in Crows Zero II the Housen boss Narumi chides a knife-wielding wayward schoolmate, “That’s not how real men do it.” — LOL. Values formation, oh wow! It’s a cop-out that provides the filmmakers with an escape route should the viewers — or the viewers’ parents, lol — ever raise a stink about the movies’ excessive violence.

So if you approach the Crows Zeros the way you would Mortal Kombat in the classroom, you won’t come away feeling shortchanged. What you shouldn’t expect is a conventional coming-of-age story where the protagonist learns what it means to be a Hero — because there’s none of that here. Not even Takiya Genji qualifies as a Hero despite Kuroki Meisa singing “Hero Lives in You” for him while the schoolyard battle rages in the Crows Zero finale. You realize that even the heroism and valor so earnestly trumpeted in these two films ring hollow — for what can possibly be heroic about two rival gangs engaging in a turf war? Neither Genji nor Serizawa steps out of their own selfish desires to fight for something greater than themselves, and so their enmity ultimately boils down to a power struggle, a chest-beating or pissing contest between two hot adversaries.

Last item on the docket: the invigorating soundtrack composed of in-your-face instrumental tracks (like “Into the Battlefield”) and showy rock anthems by The Street Beats, notably “I Wanna Change” and “Eternal Rock ‘n’ Roll.” The most memorable track from Crows Zero II is the slower — but angstier — “Torch Lighter” by the garage rock trio DOES, which plays during a pivotal sequence in the film (see embedded video above). When the desensitization to violence sets in after watching one too many romps in the mud, at least the cool and catchy tunes will perk things up for you — if ever so slightly.

As the end credits start rolling to The Street Beats’ gravelly vocals and ear-piercing instrumentals, you realize that in the Crows Zero universe, these uncannily tough and cynical students — regardless of their school — will continue fighting long after you’ve turned off your TV set and rejoined civilization (lol). It’s the one thing they’re hard-wired for, this endless cycle of battles in their grimy, graffiti-adorned, grown-up-free world. They fight to live and live to fight — and that’s just the way things are, the way it’s always been. But in truth you’ll be more than happy to leave these young punks to their merry mobocracy, forever brawling, forever battling, trapped in this lawless limbo of perpetual ass-kicking and eternal rock and roll.